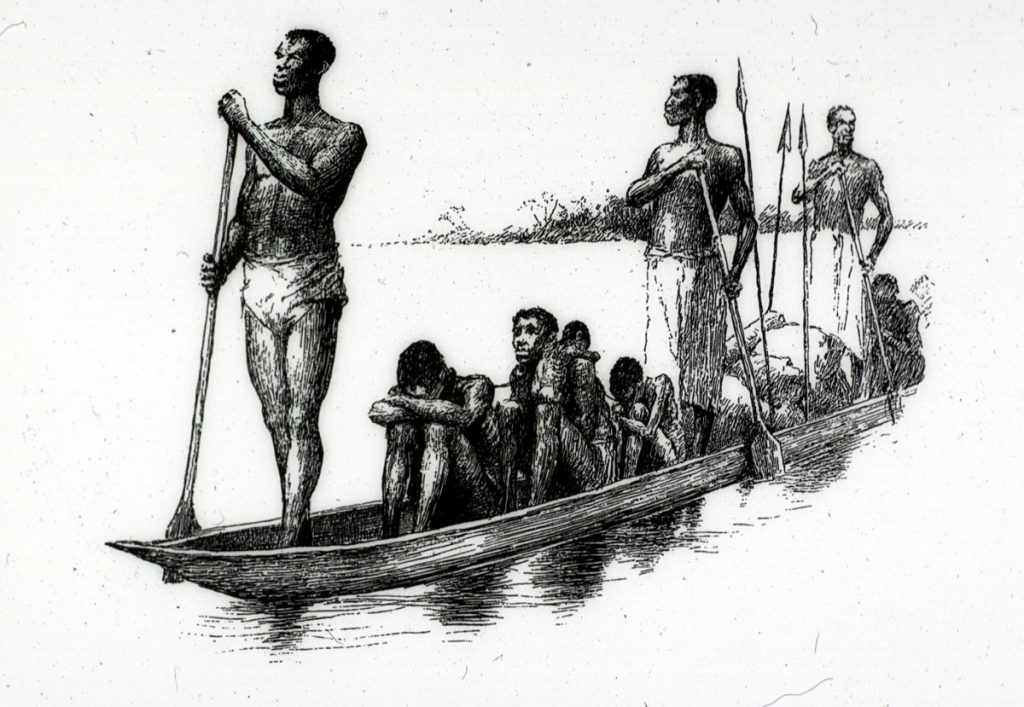

A publishing company providing Texas school textbooks describes the Atlantic slave trade between 16th and 19th centuries as bringing in “millions of workers” to plantations in America’s south.

A Texas mother and her student son recently raised questions about the curious text in the geography textbook.

BYPASS THE CENSORS

Sign up to get unfiltered news delivered straight to your inbox.

You can unsubscribe any time. By subscribing you agree to our Terms of Use

Latest Video

The publishers followed recent guidelines by the State which forced them to juggle with the grammar to accommodate current conservative political values. McGraw-Hill Education has since acknowledged that the term “workers” is a misnomer.

The New York Times reports:

The company’s chief executive also promised to revise the textbook so that its digital version as well as its next edition would more accurately describe the forced migration and enslavement of Africans. In the meantime, the company is also offering to send stickers to cover the passage.

But it will take more than that to fix the way slavery is taught in Texas textbooks. In 2010, the Texas Board of Education approved a social studies curriculum that promotes capitalism and Republican political philosophies. The curriculum guidelines prompted many concerns, including that new textbooks would downplay slavery as the cause of the Civil War.

This fall, five million public school students in Texas began using the textbooks based on the new guidelines. And some of these books distort history not through word choices but through a tool we often think of as apolitical: grammar.

In September, Bobby Finger of the website Jezebel obtained and published some excerpts from the new books, showing much of what is objectionable about their content. The books play down the horror of slavery and even seem to claim that it had an upside. This upside took the form of a distinctive African-American culture, in which family was central, Christianity provided “hope,” folk tales expressed “joy” and community dances were important social events.

But it is not only the substance of the passages that is a problem. It is also their form. The writers’ decisions about how to construct sentences, about what the subject of the sentence will be, about whether the verb will be active or passive, shape the message that slavery was not all that bad.

I teach freshman writing at Dartmouth College. My colleagues and I consistently try to convey to our students the importance of clear writing. Among the guiding principles of clear writing are these: Whenever possible, use human subjects, not abstract nouns; use active verbs, not passive. We don’t want our students to write, “Torture was used,” because that sentence obscures who was torturing whom.

In the excerpts published by Jezebel, the Texas textbooks employ all the principles of good, strong, clear writing when talking about the “upside” of slavery. But when writing about the brutality of slavery, the writers use all the tricks of obfuscation. You can see all this at play in the following passage from a textbook, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, called Texas United States History:

Some slaves reported that their masters treated them kindly. To protect their investment, some slaveholders provided adequate food and clothing for their slaves. However, severe treatment was very common. Whippings, brandings, and even worse torture were all part of American slavery.

Notice how in the first two sentences, the “slavery wasn’t that bad” sentences, the main subject of each clause is a person: slaves, masters, slaveholders. What those people, especially the slave owners, are doing is clear: They are treating their slaves kindly; they are providing adequate food and clothing. But after those two sentences there is a change, not just in the writers’ outlook on slavery but also in their sentence construction. There are no people in the last two sentences, only nouns. Yes, there is severe treatment, whippings, brandings and torture. And yes, those are all bad things. But where are the slave owners who were actually doing the whipping and branding and torturing? And where are the slaves who were whipped, branded and tortured? They are nowhere to be found in the sentence.

In another passage, slave owners and their institutionalized cruelty are similarly absent: “Families were often broken apart when a family member was sold to another owner.”

Note the use of the passive voice in the verbs “were broken apart” and “was sold.” If the sentence had been written according to the principles of good draftsmanship, it would have looked like this: Slave owners often broke slave families apart by selling a family member to another owner. A bit more powerful, no? Through grammatical manipulation, the textbook authors obscure the role of slave owners in the institution of slavery.

It may appear at first glance that the authors do a better job of focusing on the actions of slaves. After all, there are many sentences in which “slaves” are the subjects, the main characters in their own narrative. But what are the verbs in those sentences? Are the slaves suffering? No, in the sentences that feature slaves as the subject, as the main actors in the sentence, the slaves are contributing their agricultural knowledge to the growing Southern economy; they are singing songs and telling folk tales; they are expressing themselves through art and dance.

There are no sentences, in these excerpts, anyway, in which slaves are doing what slaves actually did: toiling relentlessly, without remuneration or reprieve, constantly subject to confinement, corporal punishment and death.

The textbook publishers were put in a difficult position. They had to teach history to Texas’ children without challenging conservative political views that are at odds with history. In doing so, they made many grammatical choices. Though we don’t always recognize it, grammatical choices can be moral choices, and these publishers made the wrong ones.

By Ellen Bresler Rockmore– a lecturer in the Institute for Writing and Rhetoric at Dartmouth.